WILLIAM SHIPLEY, GRANDFATHER OF CAFE CULTURE

Published by Caron Lyon,

As I edit the RSA East Midlands Nottingham and Derby conference footage I’m also learning about this extraordinary man who has inspired generations of modern thinkers.

If you think the high street coffee culture is a new think again. Try 1754!

First Published on Saturday, 14 July 2012 in http://www.think-magazine.com/cultur

Written by Mark Ellis - Mark Ellis teaches 18th-century literature at Queen Mary, University of London

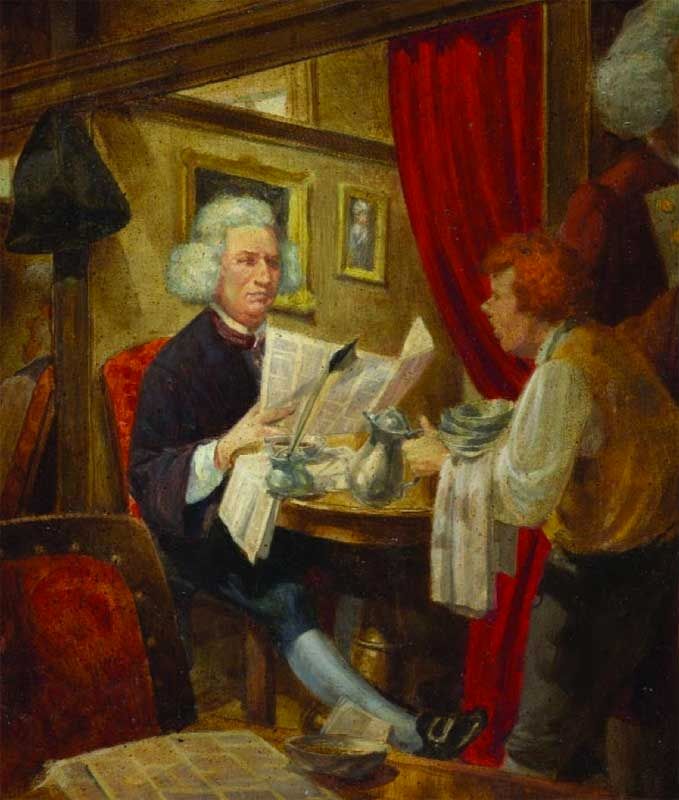

It is not surprising that William Shipley, founder of the Society of Arts, spent much of his time reading and talking in coffee houses. Such places were a lively source of vibrant and democratic debate in 18th-century London.

In 1753, William Shipley travelled from Northampton to London. The 38-year-old’s mission was to promote his philanthropic scheme for encouraging arts, manufactures and commerce by seeking the support of "gentlemen of fortune and taste".

Although he was only a provincial drawing master, and at the time virtually unknown, he was certain that his idea would benefit the whole nation if it could be developed. Lodging with a friend in Covent Garden, he threw himself into a gruelling schedule of personal calls to the houses of the nobility, gentry and merchants, explaining his plans.

Yet after several weeks campaigning, his proposal - the foundation of a society to encourage national regeneration by "promoting improvements in the liberal arts and sciences, [and] manufactures" through offering premiums or prizes had only 35 signatures of approval, and only 15 subscribers prepared to back it with money. The project could have failed before it had really begun.

But his close friends urged him into action, arguing that getting the association up and running would demonstrate what his printed proposal could only hint at. Shipley decided that the best way to do this would be to have a meeting with his fellow gentlemen activists and his loudest supporters among the nobility Lords Folkestone and Romney. Accordingly, on 22 March 1754, Shipley met with 10 men at Rawthmell's Coffee House in Henrietta Street Covent Garden. From this meeting may be traced the foundation of the Royal Society of Arts, recently celebrating its 250th anniversary.

Although the practice of coffee drinking was little more than a century old, by the mid-18th century the coffee house was central to London's social life. And London, more than any other city in western Europe, was a coffee-drinking town. Splendid coffee houses had sprung up around centres of financial, intellectual and political power, providing an arena in which the capital's cultural life could flourish. Visitors were often struck by the sheer number of such establishments (some estimated there were over 2,000) and bemused by the extraordinary fondness Londoners had for their three pleasures: coffee, company and conversation.

While staying in the capital in the 1730s, the Prussian nobleman Charles Lewis Pollnitz observed that it was a "sort of rule with the English, to go once a day at least, to houses of this sort where they talk of business and news, read the papers, and often look at one another".

The coffee house played a central role in the commercial heart of the city too, but its appeal went far beyond providing mere entertainment or sustenance.

Another commentator observed: "These coffee houses are the constant rendezvous for men of business, as well as the idle people, so that a man is sooner ask'd about his coffee house than his lodgings. They smoak tobacco, game and read papers of intelligence: here they treat matters of state... and transact affairs of the last consequence to the whole world."

As he makes clear, the coffee house was only incidentally a place to drink coffee: it was primarily a place for conversation.

Everything about the coffee house was organised to facilitate congenial discussion. In 1698, a French traveller in London, Henri Misson, remarked that coffee houses were "extremely convenient. You have all manner of news there; you have a good fire, which you may sit by as long as you please; you have a dish of coffee; you meet your friends for the transaction of business, and all for a penny, if you don't care to spend more".

The coffee room, usually on the first floor, was dominated by a long table, around which were arranged smaller booths. Each customer would take the next available free seat, while groups of friends might occupy a booth. Waiters brought coffee from the fire in small pots, pouring it into individual dishes at the table, and everyone was expected to talk to those around them. Sometimes one of the company might read aloud from the latest newspaper, pamphlet or poem, while other times the whole coffee room would join in on one debate.

The coffee house was almost unique in 18th-century society in that it allowed strangers of differing stations in life to exchange views, share business tips, discuss politics and culture, or swap gossip and scandal. Foreign visitors wondered at the spectacle of noblemen and statesmen mixing with merchants, clergymen and writers: here, status accrued through birth, wealth, or genius, was erased. All men spoke as equals, no matter what they were wearing, regardless of accent or manner of address.

As a result the place seemed a model of egalitarian or democratic principles, where everyone was expected to behave politely and talk in reasoned tones, without raised voices or personal attacks or satirical jibes. The coffee house was also noted for its serious topics of discussion.

"The English discourse freely of every thing," said one observer, "ordinary professional men discussed in detail politics the affairs of state - in the belief that their opinions mattered". Even the great Tory politician, Bolingbroke, remarked that Britain had "become a nation of statesmen. Our coffee houses and taverns are full of them".

The free and frank exchange of ideas in the coffee house has been described as the origin of what we call public opinion. Sociologists such as Jiirgen Habermas and Richard Sennett have argued that the rational, critical and egalitarian nature of coffee-house discussions helped to develop the civil society of modem participatory democracy.

But what of the coffee itself? From the outset, drinkers of coffee had noticed that it kept them awake, stimulated and chatty - quite different from the effects of the beer and ale served in taverns. Those substances, as everyone noted, made patrons reckless, lustful and quarrelsome (before it made them sleepy and then unconscious). Although Bolingbroke had compared the clientele of the tavern and the coffee house, the two venues were distinctly different: whereas the tavern was rowdy and chaotic, full of loud, garrulous and drunken customers, the coffee house was buzzing with ideas, sober, orderly and convivial.

Coffee had entered the drinks market by appealing to those who needed to be awake for long hours: students, lawyers and merchant’s clerks. These men were not always the most discerning, however. From a remarkably early date, "English" coffee was described as execrable. One satirist in 1663 had described it as "syrrop of soot, or essence of old shoes". Not only did it taste foul, it was also weak: a visiting German clergyman in 1782 remarked that his morning coffee resembled nothing more than "a prodigious quantity of brown water".

The coffee houses themselves aroused mixed feelings. While some argued that they were "the most agreeable things in London", detractors declared them "loathsome" crowded and "full of smoak". Apparently coffee-house conversations did not always meet their own high ideals, and often degenerated into argument, or idle gossip and witty badinage. As one satirist noted, these places "furnish the inhabitants with slander, for there one hears exact accounts of every thing done in town, as if it were but a village".

The egalitarian spirit of discussions did not always translate into equality of access either. The cost of coffee and the polite expectations of the assembled company, barred the poorest echelons of society. Women were effectively excluded, as it was not considered proper for them to enter such houses as customers, although the presence of a few bold women, mostly aristocrats and writers, has been recorded. In the normal course of events, the only women present were those working behind the bar.

As he approached middle age in 1754, the founder of the Society of Arts, William Shipley, was a habitué of Old Slaughter's Coffee House on St Martin’s Lane, close to the most prominent drawing school in London. There, clad all in black, he spent many an afternoon, paying sixpence for coffee or tea and reading as many of the newspapers as he could in one sitting.

In 1803, one of his first biographers described how "it was the property of his active and energetic mind ever to be studying some plan for the public advantage". To this end, he used the coffee house as a study, surrounding himself with papers and memos. Indeed, his sober, industrious and even taciturn manner nearly got him in trouble.

Aroused by fears of Jacobite insurrection after the rebels' fourth uprising in 1745, some of the coffee house's more capricious clientele imagined from Shipley's dress and demeanour that he was a spy or conspirator, and had him taken before the magistrate's court. He was liberated from their accusations by a friend, who testified that he was "one of the most loyal, benevolent, and inoffensive beings upon earth", and added, "this is the first time we ever heard it was any crime to be quiet in a coffee house".

As Shipley’s rescuer understood, coffee houses were highly regarded as places of work and business - and had been since the mid-17th century. In the City of London, near the Royal Exchange on Cornhill in particular, coffee houses had long specialised in providing a place of rendezvous for stockbrokers and merchants, who could continue their business after the official hours of the Exchange had passed.

In the 1690s, the coffee house owned by Edward Lloyd became the preferred meeting place of marine insurance brokers, thus making way for today's Lloyd's of London. Other coffee houses provided a home away from home for clergymen, booksellers, lawyers and doctors. Almost all professions had their favourite houses; a place where they could be sure of meeting someone of like-minded interests.

Scientists made good use of the coffee house too. Ever since the Royal Society "for promoting natural knowledge" was founded in 1662, its Fellows and virtuosi had, after their formal meetings, decamped to a nearby coffee house to discuss their experiments and plans without the constraints of social and institutional precedence. In the mid-18th century, scientists, medical physicians and all sorts of learned men had settled on Rawthmell's as the location for their convivial research.

Among the regulars were Dr. Richard Mead and Dr. William Birch, who belonged to a group of scientists known (rather archly) to contemporaries as "Literati". The "charms of sciences" were the main attraction of Rawthmell's according to a poem by Daniel Wray, a Fellow of both the Society of Arts and the Royal Society. Wray related that when he was "rambling tired" he would go to the upstairs room at Rawthmell's, where the "awful curtains opens wide, To seat me in that friendly jarring train". There, he says, the "sages of the Royal Society "would charm with taste and sense the listening board". As Wray's verses describe, Rawthmell's was a place both of serious-minded enquiry and entertaining discussion.

Shipley was an ordinary man without the financial means, the social connections, or the grand residence, to hold large and formal assemblies. So the coffee house afforded him a useful neutral ground, where no one man might be thought superior to any other, but also a place one associated with profound, rational conversation.

Some of the men Shipley met at Rawthmell's on 22 March 1754 reflected the established clientele: several were members of the Royal Society and several were medical practitioners. But the location enabled Shipley to extend his range to include a couple of prosperous merchants (a linen draper and a jeweller), a few clergymen and his two noblemen. The meeting was probably held in the upstairs coffee room, where they could talk without disturbance.

There, these men - united in the philanthropic goal of improving the nation - launched a practical scheme to offer real life solutions to particular problems. This was not idle philosophising on utopias. The assembled company listened to Shipley's proposals, and approved of his innovative plan to use premiums or prizes to encourage social improvement, and to raise a public subscription to fund them. In effect, the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce was up and running.

A second meeting at Rawthmell's took place a week later. Then following that, meetings were held in a room in a circulating library in Crane Court near Temple Bar, in the same courtyard as Arundel House, the home of the Royal Society.

Perhaps Shipley had thought that by holding meetings at a circulating library - in the popular imagination of that time, the home of intellectual women he might have attracted women Fellows to his society. But after six meetings there, with declining attendance and no women - they moved again to another coffee house, Peele's, at Temple Bar on Fleet Street. There, the Society announced the awards of its first premiums (to be given for drawing, and for the production of cobalt and dye).

After a year of temporary lodgings, the fledgling Society rented its first dedicated rooms in a house in Craig's Court, Charing Cross, and 20 years later, after further relocations, it moved into today's splendid, purpose-built building designed by Robert Adam in John Adam Street. Nonetheless, even though the Society's premises had become much grander, and the number of subscribers (or Fellows) had risen astronomically, the coffee house had left an important impression on its aims and objectives.

The foundation of the Society reflected (and managed to focus) the widespread interest in philanthropy and social reform in the mid-18th century, particularly among the mercantile and scientific elite. To these reformers, it not only seemed that each man or woman who had the means had a responsibility for the improvement of society, but also, that only by acting in concert could they bring about the changes they envisioned. The coffee house not only provided a location where reformers might meet, but more importantly, offered a model of a virtuous and improving collective in social engagement.

More about William Shipley - articles from across the web